In this chapter, we discuss writing news for radio and television. There is advice on how to simplify your writing and how to structure your stories to be most effective. In the following chapter we give step-by-step guidance on preparing news bulletins. In the next chapter we discuss other aspects of radio and television journalism.

______________________________________________________

Although all journalism should be a flow of information between the journalist and the reader, listener or viewer, in the broadcast media it is of vital importance that the reporter - through the newsreader or announcer - actually speaks to the audience.

It may be that you are broadcasting to millions of people, but you must write your story as if you are telling it to just one person. You should write as if someone you know personally is listening. Picture a favourite uncle or aunt, cousin or brother and imagine that you are speaking to him or her.

Your style must, therefore, be conversational and as far as possible simple.

Remember also that, unlike a newspaper story, your listeners or viewers cannot usually go back on the bulletin to hear again something they have missed - unless they resort to a catchup service. Nor can their eyes jump around within a story or a page searching for the information they want. In broadcasting the words and sentences are heard once only, one after the other, and all the information must be presented in such a way that it is understandable straight away. This is often called a linear flow of information because it goes in a line in one direction

You must help your listeners and viewers by presenting information concisely and logically.

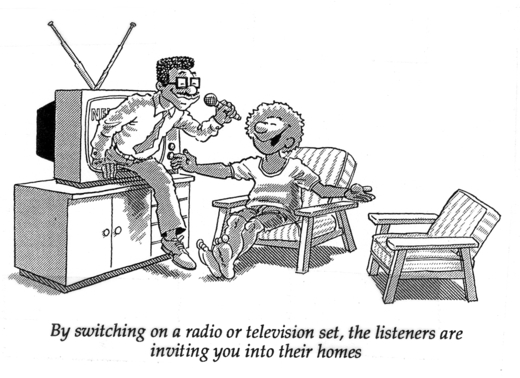

You must always remember that by switching on a radio or television set, the listeners are inviting you into their homes, their workplaces and their cars.

Write and speak as if you were talking to them as individuals, face-to-face.

^^back to the top

In practice

You should remember all you have been told about writing the basic news story. Be concise, up-to-date, stick to the main point, use the active voice, don't start with quotes and don't overload.

KISS

Keep it short and simple. You should not try to get too much information into any sentence. Although you use the inverted pyramid style of story writing, you may only be able to use one or two concepts (ideas) per sentence. You cannot get as much detail into a radio or television story as you can into a newspaper story.

You cannot expect your listener to understand the Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? of a story all in the first paragraph or even the first two paragraphs. Although as a good journalist you should not leave any essential questions unanswered, you may find that it takes all the time available for a single story to communicate only a few basic facts. It is often said that you could put all the words in a ten minute radio bulletin on one page of a newspaper.

Stick to one or two key points per sentence. No sentence should be longer than 20 words, except in unusual circumstances. Just as a mother feeds a child one spoonful at a time, allowing the child to swallow each spoonful before taking the next, you should spoon feed your listener. Give them one piece of information at a time so that it can be digested before the next piece.

Where necessary, split a long and involved sentence into two or more shorter clearer sentences, as you would in conversation.

RIGHT:

Japanese boats have returned to fish in Fijian waters.

They were banned last year because of an international row over net sizes.

Now they are back in the waters off Vanua Levu. |

WRONG:

Japanese fishing boats, which were banned from Fijian waters during an international row over net sizes last year, returned to fish in the waters off Vanua Levu on Monday. |

It may take more words, but what good is the most skilful sentence in history if the listener cannot understand it?

It might help you to write short and simple sentences if you first try to imagine how the story might appear in a newspaper headline.

Once you have reduced it to the bones of a headline, you can put some flesh on it for radio and television. Don't forget though that, whereas newspaper headlines can be incomplete sentences, without words like the and a, radio and television news must be in complete sentences.

Look at the following example and notice how we take the details in the information, strip it down to the bones by writing a headline, then add words to turn the headline into a complete sentence, suitable for radio or television.

INFORMATION:

A contract for the construction of a new road between Madang and Lae has been awarded to a Korean company.

HEADLINE:

Koreans to build new road

INTRO:

A Korean company is to build a new road between Madang and Lae.

^^back to the top

Use up-to-date tenses

The single greatest advantage of broadcasting is immediacy. You can inform your listener as an event is happening, or immediately afterwards, without waiting for typesetters or printing presses. Do not waste that advantage.

Keep all tenses as up-to-date as possible. Use the present tense or the tense nearest to the present and, whenever possible, use a continuous tense to tell your listener that a thing is still happening, as they listen.

Compare the tenses in the following examples. The verbs are in italics.

RIGHT:

The Prime Minister says he expects an increase in imports this year. |

WRONG:

The Prime Minister said he expected an increase in imports this year. |

RIGHT:

Leaders of the main opposition parties in Fiji have been meeting. |

WRONG:

Leaders of the main opposition parties in Fiji met over the weekend |

There is no room for words such as "yesterday", "last week" or "last Monday" in the intro of a broadcast news story. If the date makes the story seem old or stale, hide it down in the main body of the story.

^^back to the top

Do not use quotes

Do not use quotes in radio or television stories. If you want your listeners to hear the words as they were spoken, record them on tape and use them as actuality (the actual sound of something or someone, sometimes also called audio). This ability to hear people speak is one of the great benefits of broadcasting.

Also, quotes in broadcasting cannot work as they do in print, where the readers can see the quotation marks. It is just as effective to turn quotes into reported speech (see Chapter 8: Quotes).

Bad journalists try to get round this rule by using the words "quote" and "unquote" at the beginning and end of direct quotes. This sounds clumsy. It is much better in radio to rewrite quotes in reported speech. Compare the following sentences:

RIGHT:

The chairman said it was a crying shame. |

WRONG:

The chairman said: "It is a crying shame." |

|

WRONG:

The chairman said, quote: It is a crying shame - unquote. |

If you feel the need to stress a certain word or phrase in reported speech, to emphasise that these are the actual words used, underline them so the newsreader can add the stress with their voice. Again, it is better to use actuality where possible.

Some journalists mistakenly think that they will be safe from defamation if they add "quote ... unquote" around danger words. In law, it does not matter whether words are in quotes or reported speech; they could still be defamatory. (See Chapter 69: Defamation.)

Quotes on screen

The only time you would normally use quotes in television is when you present them as text on screen. This most commonly happens when you do not have footage and it is important the the viewer can see the exact words used, for example when quoting a judge from a court case where audio or vision is not available. These quotes are usually kept very short and given in large, easy-to-read type, punctuated as they would be in print media. It is also usual to read them out aloud; radio and television do not like silences.

Because on-screen quotes should be as concise as possible, it is permissible to miss out unimportant words or phrases, as long as this does not change the overall meaning or grammar of the sentence or excerpt. You must show that content is missing by replacing it with ellipses. An ellipsis is a punctuation mark consisting of three dots (with a fourth dot if it at the end of a sentence). On-screen ellipses can be written on their own or inside square brackets, depending on your house style, i.e. either ... or [...]. Check which is correct for your organisation. They are not read out aloud when narrating the on-screen excerpt.

^^back to the top

Put attribution first

Attribution in radio and television goes at the front of a sentence, as it would if you were talking to that favourite aunt. This is unlike traditional newspaper style, which commonly puts attribution such as he said at the end of the sentence, after the quote. In newspapers, readers can see both the quote and the attribution together. In radio and television, your listeners need to know who was speaking before they can judge what was said. Remember the linear structure of broadcast news.

Compare the following sentences. The attribution is in italics.

RIGHT:

A senior government economist says that people in Papua New Guinea are paid too much. |

WRONG:

People are paid too much in Papua New Guinea, a senior government economist said last night. |

By putting the attribution up front, you are also making your sentence more active, important for broadcast news.

^^back to the top

Avoid unfamiliar words

If a newspaper reader does not understand a word, he or she can return to it and maybe look it up in a dictionary before proceeding to the rest of the story. Your listeners cannot do this.

By the time they have worked out the meaning of an unfamiliar word, the story will be over and they will have missed all the other details.

If you have to use an unfamiliar word or name, you must not hit your listeners with it without warning. You should never put it as the first word in your paragraph, but work your way towards it over familiar ground.

In the following examples, the unfamiliar words are in italics.

RIGHT:

In Mexico, the volcano Popocatepetl has erupted again.

It showered lava and ash for 50 kilometres around. |

WRONG:

Popocatepetl, a volcano in Mexico, erupted again yesterday, showering lava and ash on the ground over a radius of 50 km. |

People's names can cause problems too, unless they are familiar. For example, the name of your Prime Minister or President may not cause problems, but an unfamiliar name might, as in the following example:

RIGHT:

A school inspector in the East Sepik says teachers don't listen enough to their students.

The inspector, Mr Arianthis Koloaloa, says ... |

WRONG:

Mr Arianthis Koloaloa, a school inspector in the East Sepik, has criticised teachers for not listening to their students. |

^^back to the top

Repeat important words

Because radio and television listeners do not pay attention all the time, and because people often switch on their sets half-way through a bulletin, it is important that you repeat the essential features several times in the story.

They might be half-listening to the radio or TV until something - perhaps a word relevant to them or their interest - triggers their attention. They then 'tune in' with their mind but, because of the linear nature of broadcast news, they cannot go back and retrieve any words they have missed. So repeat important words at least once in the story.

In the following example, the words Korean, Madang, Lae and road are repeated:

A Korean company is to build a new road between Madang and Lae.

They estimate it will cost more than one-hundred-million kina.

Work on the new Madang to Lae road should begin in August.

The Prime Minister, Mr Rabbie Namaliu, says the Koreans were awarded the road contract because of their years of experience.

Of course, too much repetition can be boring, so do not overdo it. A simple tip is to cover the intro and see whether or not you can still understand the story from what is left. Try it with the example above.

^^back to the top

Keep punctuation simple

Keep punctuation as simple as possible. In broadcast news, punctuation marks are not only there for grammatical reasons. They also give the newsreader clues on breathing.

In general, the only punctuation marks you need are the full stop, comma, question mark and dash. Some writers like to use a series of dots to denote a pause, as in the following example:

The Prime Minister... speaking at a business lunch... said the economy is looking brighter.

Where two words go together to form a single concept, hyphenate them whether or not it is grammatically correct to do so. For example, write mini-market, winding-rope, pocket-book.

^^back to the top

Simplify numbers

Numbers should be included to inform, not to confuse - either the newsreader or the listener. Wherever there is the possibility of confusing the newsreader, write the number in full.

RIGHT:

two-million, nine-hundred-and-eighty thousand, and two. |

WRONG:

2,980,002 |

Better still, round off large figures, so that the example above becomes "almost three million". This simplifies matters for both the newsreader and the listeners.

The same rule applies to fractions. Write them in full, for example one-half, three-quarters etc.

With money, spell out the units, so that $1.50 becomes "one-dollar-fifty".

Many newsreaders even prefer the date to be spelt out, as in the following:

RIGHT:

The 1st of March, 2007. |

WRONG:

March 1, 2007. |

^^back to the top

Avoid abbreviations

As a general rule, avoid abbreviations. You can, of course, use "Mr", or "Mrs" in your script, but do not abbreviate other titles.

Where the initials of an organisation are read as a word, write them as such, for example Nato, Asean, Apec.

But if they must be read individually, separate each letter with a dot, as in U.N., P.N.G. or Y.M.C.A.. Some broadcasters prefer to hyphenate the letters, to make it even clearer that they must be read out separately, for example P-N-G.

The first reference must be written in full unless the initials are widely understood on their own - as are the three examples above.

Do not use the abbreviations a.m. or p.m. There is always a better way which tells your listeners much more. Phrases like "this morning" or "tomorrow afternoon" mean much more to most listeners. See how much clearer the correct sentence is in the following example.

RIGHT:

The rocket was launched at three this morning. |

WRONG:

The rocket was launched at 3 a.m. today. |

^^back to the top

Give a guide to pronunciation

Pronunciation is a very large field. Most newsrooms should have a pronunciation guide for place names and other difficult foreign words.

Good dictionaries should give you correct pronunciations, but if you are in doubt, check with a senior journalist or someone who is likely to know the correct pronunciation. For example, if it is the name of a species of fish, check with a fisheries officer.

When writing an unfamiliar word for the newsreader, make their task as simple as possible by writing it phonetically. For example, the state of Arkansas should be written as ARK-en-sor; the French word gendarme becomes JON-darm, placing the stress on the syllable in capital letters.

Do everything you can do to make the message clearer.

Simplify your script

Readers in English and many other langauges scan text from left to right. It may seem smooth but the eyes actually move forward in short bursts, called saccades. When they come to the end of the line their eyes leap all the way back across the page to the start of the next line. This momentary flicker of the eyes - less than a fraction of a second - is where reading errors often occur.

Even the most professional script reader cannot remember all the words at the start of each line, so in the small fraction of a second while their eyes are travelling back across the page they do not know what is coming next. To avoid the listener hearing this hesitation, it is good practice to use this moment at the end of a line for a syntactical pause, perhaps a full stop, comma, semi-colon, dash or ellipsis (three dots). Punctuating this way may leave some lines much shorter than others, but no-one apart from the script reader will know this. Consistent lines lengths are really only important in newspapers, magazines or books.

In radio and television, it also helps if the script has a clear space between sentences (perhaps a blank line), so the reader can find the start of the next sentence slightly more easily in the extra space.

Another error to avoid is splitting common phrases, titles or names between the end of one line and the start of the next. While in some cases it might make the transition to the new line more predictable, it is open to mistakes. For example, if the script ends a line with the word "United", the reader has to wait all the way to the start of the new line to discover whether the next word is either "States of America", "Kingdom" or "Arab Emirates". This will be enough to throw the reader off balance.

Interestingly, when a script reader comes across an error or obstacle it only becomes apparent a few words later, when they actually stumble over it. This is the time it takes for the reader's brain to process and become aware of the error, at which point they actually stumble. When you are check reading your script aloud and you stumble, go back over the previous few words and you will find the problem word or phrase there. Sometimes it can be as little as a minor spelling error you did not detect when you were writing the script.

This advice on simplifying your script applies to both paper scripts, on-screen readers or teleprompters, though with the latter other factors must also be considered, such as the size of the text and the rate at which the words scroll up on the screen. We talk more about this in the next chapter.

^^back to the top

Writing for television

Although most of the rules for broadcast writing (such as KISS) apply to both radio and television, there are a few additional factors to remember when writing for television.

Making television news is a more complicated process than producing radio news - which can often be done by one person. Television always involves several people, performing specialist tasks such as camera operating, scriptwriting, bulletin presenting, directing, studio managing, lighting and sound mixing.

Television also involves two simultaneous methods of presenting information - sound and vision. Of the two, vision is usually the most effective in giving details quickly. For example, you could take several minutes to describe a crash scene which can be understood from a ten-second film segment. The words in television usually support the pictures, not the other way round. That is why television reporters usually write their scripts after they have edited the videotape (or film). You usually have to write your script so that the words match the pictures which are on the screen. This requires good language skills, especially in simplifying complex language. If a newsreader has to read your script live - perhaps from an autocue - it will help them if you keep the words and grammar simple and the sentences short. (An autocue – also called a teleprompter - is a device which projects a magnified image of the script on a clear screen in front of the camera lens, in such a way that only the presenter can see it. It is invisible to the viewers at home. It is used so presenters do not need to keep looking down at their scripts.)

Of course, the words become more important when there are no pictures to illustrate the story, only the sight of the newsreader's head and shoulders. But you should always try to think of ways of presenting some of your information visually, otherwise you are wasting half of your resources (the vision). For example, if you are telling about a new tax on beer, you will probably simultaneously show pictures of a brewery and of beer being produced and consumed. You might also want to show a graph showing how beer sales and taxes have increased over the past few years. And you may want a clip of the relevant minister explaining why he is increasing the tax.

As well as being aware of how your words will support the pictures, you must also consider the effect the pictures will have on your viewers' ability to listen to the words. For example, if you have some very dramatic pictures of an explosion, you should not write your script in such a way that the important facts are given while viewers have all their attention on the picture. Perhaps leave a couple of seconds without any commentary during the explosion, then bring your viewers' attention back to the words gradually. Remember that every time you change the picture on the screen, your viewers' attention is distracted away from the words while they concentrate on the new image. Bear this in mind when writing your script to fit the edited pictures.

Because television viewers have to concentrate on both sight and sound, you cannot expect them to concentrate on lots of details while there are interesting pictures on the screen. So if you want to give some very important details, either do it when the camera returns to a picture of the newsreader, or do it through graphics such as maps, diagrams, graphs or tables or through captions.

^^back to the top

Captions

The names and titles of speakers are usually written on the screen in captions. These must be simple and clear, so that your viewers do not have to spend much time reading them. Remember too that your viewers may not all be able to read. If you know that literacy rates are low among your audience, putting the written word on the screen will not alone explain essential details. For example, in countries with high literacy rates, television newsreaders or reporters use only captions to identify speakers. You may need to both present a caption and also read the name aloud.

Subtitles and closed captions

Subtitles and closed captions are visual versions of the words that are being spoken on the television screen. Closed captions are presented in the language being spoken so the deaf or viewers hard of hearing can follow what is being said. Closed captions may also present text clues about what other sounds are present, such as [loud bang] or [sombre music]. Subtitles are used to translate foreign language content into the language of broadcast. For example, English language content might be translated into Tagalog for viewing in the Philippines.

Closed captions and subtitles usually run along the bottom of the screen so viewers can read them while still watching the pictures and listening to the words being spoken. Both generally need to be prepared beforehand and they require concentration from the viewer, so they should be done professionally if possible. There are automated captioning applications that use artificial intelligence (AI) to generate the text, but these can be unreliable and frequently produce laughable mistakes, especially when turning names into text.

On radio or to avoid having to use subtitled translations of words spoken in another language on television, it is possible to over-dub what the speaker is saying by fading down the original sound and getting another voice to read a translation over it, either a fellow journalist or a professional voice actor. Simpler still is to fade down the words being spoken so they can barely be heard then the newsreader (or reporter) can summarise what is said in reported speech.

^^back to the top

Stand-ups

One final word about writing for stand-ups. These are the times when a reporter speaks directly into the camera at the scene of the story. Each stand-up segment in news is normally about 10 or 20 seconds long, meaning that it can contain several sentences of spoken word. Some reporters write the words they will say in sentences on a notebook then read them out in front of the camera. However, this means that the reporter cannot look into the camera while also looking down to read from the notebook.

It is better either to memorise the sentences then put the notebook to one side or to remember only the key words you want to use then speak sentences directly into the camera. In both cases, it helps if you keep the language simple and your sentences short. You must also avoid using words which might be difficult to pronounce. If you try to say "The previous Prime Minister passed away in Papeete", you will get into difficulties because of all the "p" sounds. Rewrite the sentence as "The last Prime Minister died in Papeete."

Listen to your listeners or viewers

Radio – and to some extent television - is a form of conversation between broadcasters and their listeners (or viewers). While in its early years radio listening was almost obligatory in many countries, today citizens have much wider choices of media and so broadcasters cannot take them for granted.

Broadcasters and their audiences have the technologies to make their conversations two-way affairs, which better serves the interests of both content producers and its consumers. Broadcasters make the kind of programs that audiences say they want and the audiences get content better suited to their needs and desires. It is therefore important that broadcasters listen to their listeners and viewers. Find out how well your programs are received and if there was anything important missing. How was the presentation style? Were essential questions left unanswered? What do your listeners want more of? What less?

Tools such as audience surveys are useful in getting numbers to analyse services in general but modern technologies make it possible to get instant, individualised feedback to each program, segment or news story. We talk more about this is our chapter on New media and social media.

TO SUMMARISE:

Follow these simple writing rules:

- KISS - keep it short and simple

- Try to avoid quotes on radio or in television scripts

- Avoid unfamiliar words

- Repeat important words

- Keep punctuation simple

- Simplify numbers

- Avoid abbreviations

- Show how to pronounce difficult words

- Simplfy your script

- Find out what your listeners or viewers like or dislike about how your information is presented.

This is the end of the first part of this two-part section on radio and television. If you now want to read on, follow this link to the second section, Chapter 49: Radio and television journalism

__________________________________

For tips on how to conduct on-camera

interviews, go to Media Helping Media:

^^back to the top