In this and the next chapter, we give you advice on how to cover sudden events which bring death and destruction to people. In the previous chapter we explained how to prepare both yourself and your organisation to cope with any emergency. In this chapter we talk about how to get to the scene, what to do there, how to write reports and get them back to your newsroom, and how to organise news staff efficiently. Finally, we discuss the sensitivity needed when reporting death and disaster.

_______________________________________________________

In a major disaster, you will need reporters both at the scene and in the newsroom. Reporters at the scene can get many facts immediately, describe the scene, and interview the rescuers and eyewitnesses. But do not send all your reporting staff to the scene. Keep some in the newsroom to follow other leads and put the stories together. If necessary, call off-duty staff in to work. A good journalist will always be happy to be involved.

Getting to the scene

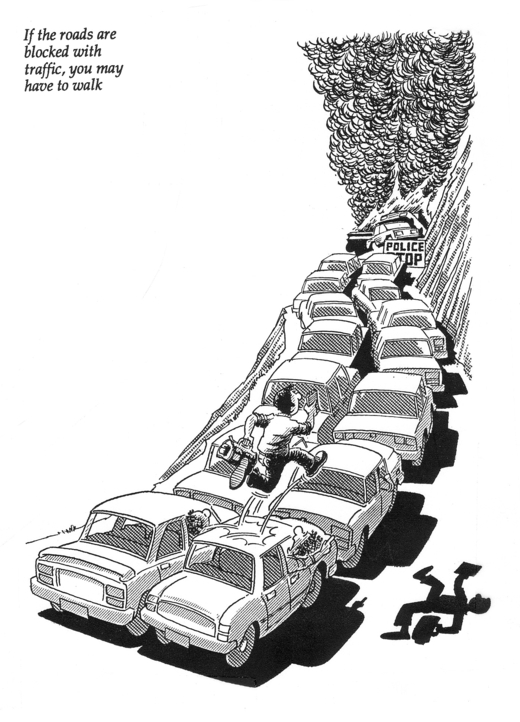

You may have problems getting to the scene of the emergency. If it is local, you might be able to travel by car or taxi, but you may find that roads are closed by police because of the emergency. This is where preparation can help. You will probably find that an official pass or mentioning the name of a senior officer at the scene will help you get past any roadblocks. If the roads are blocked with traffic, you may have to walk or hitch a lift from a passing emergency vehicle (again, it helps if you are known by the emergency service staff).

For longer distance assignments, good contacts at the airline booking office will help with travel arrangements and might even get you a seat on a plane which is fully booked. Your news organisation should have at least one member of staff who is responsible for emergency travel arrangements. That person might be the editor's assistant or the newsroom secretary.

If you cannot travel by scheduled airlines, perhaps you can use your contacts to hitch a lift in a coastguard boat, a police car or an army helicopter. Even if the situation seems hopeless, always ask. If the senior officers do not give permission, perhaps a friendly pilot might quietly take you on board.

Always think about how far forward you should go, especially when travelling into a disaster area. Although you need to get as near as possible to the centre of the action, you will always need to get your story out again. If you are working for a weekly magazine, you may have two or three days to return with a story. But if you are working for radio, television or daily newspapers you will need to get your story out within hours. In such cases, never travel too far away from your means of communication, such as telephones or radios. Sending two or more reporters to the scene might solve this problem.

Although many reporters are good at getting to the scene quickly, many do not think about getting back. Remember you may have to get back to the newsroom to write your story or you will need to send back film or tapes. Sometimes two or more reporters can share these jobs, but you might find a courier is better, someone paid to deliver things in a hurry. Many television stations have their own couriers, usually equipped with motorcycles to get through heavy traffic.

If you are travelling a long way to the scene, perhaps arrange with someone - maybe even the friendly pilot - to carry your finished tapes or films when he returns to base, then your newsroom can collect them from him. These must be people you can trust. If they are already good contacts, they will be more reliable.

^^back to the top

At the scene

On arriving at the scene, the first thing you must do is quickly assess what is happening so that you can inform your newsroom and send back a first story. This will be most important for reporters from radio, television or daily newspapers which are approaching their deadlines.

Take a quick look around and try to find people in authority at the centre: perhaps the chief fire officer or the leader of the rescue team. Introduce yourself quickly and correctly and promise you will not take up their time. Ask simple questions to find out what has happened and what is happening now. Ask about the dead and injured, what rescue attempts are being made and, if relevant, what was the possible cause. Do not enter into a debate with busy people, or you may be removed from the scene. Radio and television reporters should record such interviews.

Spend five minutes quickly writing a short story in your notebook. Contact your newsroom and let them know the main facts, so they can assess what they need to do, such as sending more reporters, changing programs or adding extra pages to the newspaper. Send them your short story for a special news flash or a stop press. Agree on a time when you will telephone them again, perhaps in half-an-hour.

Now you can get more details and start to build up your major story. Talk to as many people as possible without getting in the way of rescuers.

Look busy and show that you are doing your job professionally. Wear some official identification tag, even if it is only your newsroom security pass, and stay clear of any crowds of sightseers. If you are mistaken for a spectator, you may be removed if police clear sightseers from the scene. Once you have been seen talking to senior officers, other rescue staff will probably leave you alone to do your job.

^^back to the top

Your main tasks

The scene may be chaotic, but you have some essential tasks to do. These will include the following:

Notes and recordings

Make lots of notes about what you see and what people say. Radio and television journalists should do a lot of recording but never use all your supply of tapes at once. Save some in reserve in case something unexpected happens, such as a second explosion, another tremor or the discovery of someone trapped alive in the wreckage.

Eyewitnesses

Look for eyewitnesses, people who were there at the time of the event and who can describe what happened. Get their personal details such as names, ages and what they were doing at the scene. They may be in a state of shock, so be gentle when you ask questions. Try to get them to explain what happened in their own words.

Keep contact

Keep contact with the people in charge or who seem to know what is going on. You can leave them while you do other interviews, but always know where they are in case something happens and you need more information from them. Again, a second reporter will be useful to share the burden.

Inform your newsroom

Keep your newsroom informed of latest developments and contact them on a regular basis. There is nothing more frustrating for a news editor than to lose contact with journalists in the field and not know what is happening. For example, once you know where the injured are being taken, tell your newsroom so they can send another reporter to the hospital.

The scenes of disasters and other emergencies can be chaotic, with events changing minute-by-minute. Many reporters are afraid that they will miss something while they are contacting their newsroom. If the activity seems to slow down, take the chance to contact your newsroom. If you have to leave the scene, arrange with journalists from other news organisations to "keep an eye on things". They too will probably need to contact their newsrooms, so you can return the favour for them. Try where possible to share information, but you may also be in competition with some of the reporters there, for example reporters from a competing newspaper.

Find colour

Look for things which might add colour to your report. By colour, we mean observations which may not be essential to the story, but which help your readers or listeners imagine what is happening. For example, look for pictures which will illustrate the scene. One of the most famous pictures of an aeroplane crash showed only a child's doll lying in the mud beside a shattered aeroplane seat. Radio reporters should listen for sounds, such as the sound of an electric saw being used to cut through wreckage or the shouts of rescuers.

^^back to the top

Tasks in the newsroom

Although your organisation should always try to send a reporter to the scene of a disaster or other major crisis, there is plenty of work for journalists left in the newsroom. There are more details to gather, stories to write and pages or bulletins to put together.

Assign tasks

The news editor or chief of staff should organise journalists to do different tasks. Someone - or a team of writers - must be responsible for the final story or stories, either writing them or checking how separate stories fit together in the overall coverage. If the news editor and chief of staff are busy with other jobs, one person must take responsibility for overall coverage.

Someone must keep the rest of your news organisation informed. The printing manager will need to know about new deadlines or extra pages; the program presenter will need to know if there will be extended news bulletins. The more people know, the better they can help.

Gather more details

Although the reporter at the scene can do a lot, they cannot usually do everything needed for a story. At least one reporter must be given the job of getting additional information, background details and comments. They can keep in touch with the emergency control rooms for details. They can find out from experts or from your cuttings or tape library details about previous disasters. They can contact people such as ministers or aid agencies for comments and details on what help can be given to the victims.

Reporters may need to be sent to airports or hospitals to report on how casualties are being received and treated.

If it is a major disaster, ask the emergency services for a special telephone number which people can ring to find out about friends and relatives who might be victims. Once you print or broadcast this telephone number, it might stop members of the public telephoning you for details.

^^back to the top

Writing the story

There may be only one story (such as in a car crash), but major disasters usually need several separate stories to explain all the aspects. There will usually be one lead story summarising the overall picture, then several other stories concentrating on different angles, such as the rescue operation, eyewitness accounts, background history and messages of condolence.

Style

Keep your writing clear and simple. Keep your sentences short so that they are easy to understand quickly and so that they can easily be moved around within the story if you re-write it to update it. Always do one final check to update the death toll just before you publish or broadcast.

By-lines

It is usual for newspapers to print the names of reporters involved in a major story, usually in by-lines, or in a box beside the story if the team was large. Most reporters work extra hard during a crisis and deserve some special recognition. Sub-editors should make sure that they name all the reporters who worked on the stories. Such recognition also helps to strengthen the links between reporters and their contacts if the stories are accurate and well-written.

Language

Keep your language simple, using words your readers or listeners can understand easily. Stories about death and disaster are usually exciting to read. Do not kill the story with slow and heavy words. Aircraft do not "impact with the inclined slope of a hill during a period of limited day-time visibility", they "crash into a hillside in fog".

Do not use complicated technical words or jargon which is only used by emergency service staff. For example, ambulance officers talk about a person being "DOA" meaning "dead on arrival" (at hospital). In plain English, write that a person has "died before reaching hospital" or, if you know they were still alive when they were dragged from the wreckage, you can say they "died on the way to hospital". (See Chapters 10 and 11 on language and style.)

Of course, you should not avoid all technical terms. For example, when reporting on an earthquake, you have to mention how strong it was. Earthquake strength in measured on the Richter scale (pronounced: RIK-ta) and given as a number and point, such as "7.5" (read as "seven-point-five" on radio and television). The scale is calculated in such a way that every increase in one whole number on the Richter scale shows a ten-fold increase in the strength of the earthquake. Any earthquake above 5 on the Richter scale is severe but damage depends on a lot of factors such as the structure of the earth at certain points and the types of housing affected.

Avoid vague words, especially adjectives and adverbs (the words which describe the nouns and verbs). It is always better to give details than to give vague impressions. For example, instead of writing "Many people died when a massive volcano on Rubadub Island exploded doing enormous damage", give the facts and write: "More than 60 people died when a volcano on Rubadub Island erupted, splitting the island in two. The death toll is likely to rise as rescuers search for missing islanders".

Give the facts

Try to answer all the obvious questions your readers or listeners will ask. Remember WWWWWH - Who? What? Where? When? Why? and How? You may not be able to answer the Why? question straight away, because details may not be clear or blame has not been proved.

Write blocks of similar material together so that they can easily be moved around the story. For example, keep the detailed description of the scene together. Keep the report of what is happening at the hospital together. However, you will need to use some material in different places, such as in the intro, so that the whole story makes sense.

You need to give the following kinds of details:

Casualties - numbers of dead and injured, types of injury, where casualties were taken, any well-known names, people who escaped.

Damage - the extent, and estimate of the cost, what kind of damage, any well-known buildings.

Description - of the event itself, eyewitness stories, the scene afterwards.

Rescue and relief - the people involved, the action being taken, the facilities, any problems (such as weather), evacuations, any acts of heroism.

Cause - what the experts say, eyewitness accounts, who sounded the alarm and was there any warning?

Follow-up action - will there be post mortems or inquiries, legal action, rebuilding?

Do not exaggerate

Let the facts speak for themselves. If you exaggerate you will make your story soft and vague. You could also cause unnecessary alarm and panic in your readers or listeners. If fires have destroyed forest in a small corner of Warang Province, it would be wrong to write: "Warang Province is ablaze."

Try to keep your emotions under control. Although you may become emotionally involved in the event, you must write your stories without putting in your own feelings. For example, you might find the scene of an earthquake extremely distressing. You might see the bodies of men, women and children lying in the broken remains of their homes. Do not write about how bad it makes you feel. Describe the scene carefully in simple language. If you write well, you will take your readers or listeners to the scene, allowing them to feel the tragedy with their own emotions.

^^back to the top

Follow-ups

Crises, accidents and disasters do not end just because you have finished reporting them. The effects of major tragedies are felt for a long time. You should write follow-up stories to keep your audience informed about such things as: people who later died of their injuries; accurate details of the cost of damage; any new relief action; the results of any inquiries or inquests; how the event changed the lives of survivors.

Bigger disasters will need longer follow-ups. For example, if a mudslide destroyed an entire mountain village, it could take months before survivors are able to rebuild their homes and replace their food gardens; it could be years before all the scars are gone. Make a note in your newsdesk diary to follow-up their story, perhaps in three months time, perhaps on the anniversary of the disaster. Find out what has happened to the survivors. Especially find out what has happened to all the promises of help which might have been made at the time.

Anniversaries

For major disasters, you might want to produce special features or documentaries on major anniversaries, such as the tenth or the twentieth. It will help your work if your newsroom has saved material such as photographs, tapes or films. Although no radio and television station can afford to keep the tapes from every story, they should keep tapes and film from major disasters, so they can be used again in the future.

^^back to the top

Sensitivity

When reporting on death and disaster, you will meet people who are hurt, both physically and emotionally. These people could be survivors or the friends and relatives of the killed and injured. You must be sensitive to their pain.

At the scene

Do not interfere with rescue operations and do not try to interview people who are obviously hurt, unless they clearly show they want to be interviewed.

Be careful with names

You may know the names of people killed or badly injured, but you should not print or broadcast them until you know that their closest relatives have been told. It is very cruel to learn of the death of a loved one from a newspaper or bulletin. It is usual to wait until the police tell you that the next-of-kin have been told.

In some societies, it is wrong to speak or write the names of people who have died. In Australian Aboriginal communities, it is wrong to show images of the dead during the time of mourning for them. Be sensitive to such issues.

Pictures and sound

Although you should give the facts as accurately as possible, you can cause grief by doing it. Be careful in choosing pictures to illustrate your story. The body you show with all its arms and legs ripped off was somebody's relative or friend. You have to balance the need to show such pictures against the duty not to cause unnecessary grief. There is no easy answer. If you have to show such scenes in a television program, warn the viewers beforehand that “the following report may contain images distressing to some viewers”.

Sounds too can have both good and bad effects. The sound of a child screaming as she is cut from the wreckage of a car may make powerful radio, but it will also be intruding into the grief of many people. (See Chapter 61: Taste and bad taste.)

Blame

Be careful about laying blame on anyone for an accident or disaster. If it was caused by someone's action or inaction, let the courts decide. If you accuse someone wrongly, they can sue you for defamation.

Even the words you use can be seen as laying blame. For example, if you write that "the car crashed into the bus", you are blaming the car driver. Unless it is totally clear who was to blame, say something like "the car and bus collided". Of course, it would be silly (and wrong) to say that they "collided" if the bus was standing still with its engine switched off. Similarly, cars do not "collide" with trees, they "hit" them.

^^back to the top

Debrief and learn

Because you cannot fully learn a new task in journalism without doing it, the best way of learning how to report on a crisis, accident or disaster is by attending one. Read this chapter again after you have finished such a reporting assignment and think where you could have improved your work.

Better still, whenever you complete a major reporting assignment, sit down with colleagues and senior journalists to discuss what you all did right and wrong. These debriefing sessions can be a time when the editor can say thanks for a good job. They can also make you better prepared for the next time.

^^back to the top

TO SUMMARISE:

You and your organisation must be well prepared; you must establish emergency procedures before they are needed

Good contacts with the emergency services are vital

Regularly check all equipment, to make sure that it is working properly

Always try to plan ahead; think of problems which might arise and ways of solving them

Keep the newsdesk informed of what is happening at all times

Keep your stories simple and do not put in your own emotions

Be sensitive to people's suffering

Think of follow-ups

^^back to the top

>>go to next chapter