In this chapter, we discuss the challenge facing journalists in reporting science and technology. We advise on the ways of preparing yourself and of using experts to make your task easier. In the following chapter we discuss ways of writing bright, interesting stories and conclude with some solutions to common problem areas.

_______________________________________________________

Many journalists are afraid of reporting on science and technology. They think these subjects are either too complicated for them to understand or too boring for their audience. This does not need to be so. With the proper preparation, and by following a few simple rules, reporting science and technology can be one of the most interesting jobs a journalist can do. And it certainly does not have to be difficult.

What is science and technology?

Like good scientists, let us start by defining what we mean by science and technology.

Science is the organised study of Man and the universe by means of observation, measurement and experiments. Scientists try to find the rules which govern the universe.

Technology is the practical application of science.

Although there is a distinction between them, science and technology overlap in so many ways that we will treat them as a single field in this chapter.

We discuss reporting on agriculture, fisheries and forestry at the end of this chapter.

Science and technology have always played an important part in Man's existence, even though our ancestors may not have called their knowledge and skill by these names. When our ancestors decided on the best season for planting yams, they usually took into account the season, the weather, the amount of water available, the fertility of the soil and a host of other factors. This was simple science. When they dug the soil with a pointed stick or built paddy fields, this was technology.

Today, science and technology have become more complex as we learn more about our universe and develop ways of changing it. Also, because there is so much more knowledge available, scientists are forced to specialise in particular areas, to keep pace with advances.

Science and technology today range all the way from basically theoretical subjects such as quantum physics to more practical subjects like medicine, agriculture and engineering.

Some subjects, such as agriculture and medicine have everyday practical benefits for mankind. Others, such as astronomy, help us understand our universe but do not have an immediate practical effect on us.

There is a host of other fields such as physics, chemistry, zoology, marine biology, geology, ecology, medicine, psychology, mechanical and electrical engineering - the list is enormous and growing every year. Science and technology is too important for journalists to ignore.

^^back to the top

The challenge facing journalists

Although large news organisations often have reporters with some scientific education to specialise in writing about science and technology, in most smaller newspapers, radio and television stations, this task is left to general reporters. Whether you are a specialist or a general reporter, you should remember the following basic facts principles:

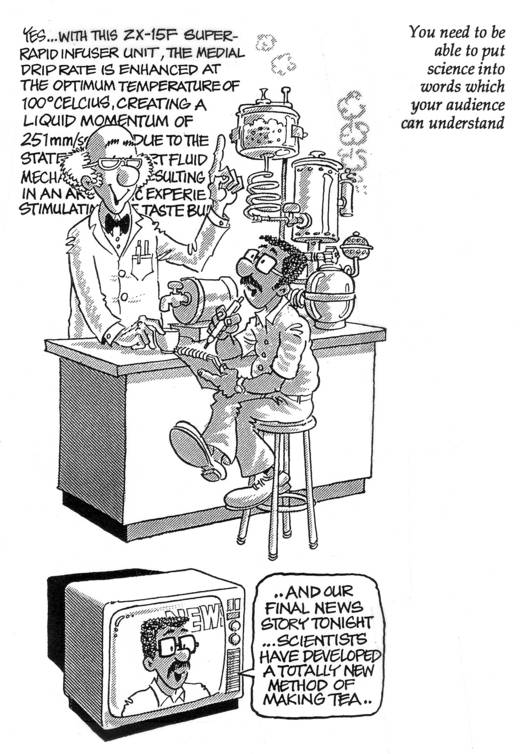

- You are a bridge between the world of science and your community. You do not need to know as much as the scientists. You simply need to be able to put the relevant parts of their knowledge into words which your audience can understand.

- You do not have to understand the whole of any field of science yourself, but you must not write anything you do not understand. If you write something you do not understand, you risk making errors.

- Although the aim of scientists is precision, and the aim of journalists is simplicity, there should be no conflict between the two. You must be able to express the precise details of science accurately in simple terms. That is the real challenge of reporting science and technology.

- Most science and technology will have human applications. For every story, you must ask yourself: "How will this affect my readers' or listeners' lives?" Your job is to describe what those affects are. Remember the four criteria for what makes news.

- Some science, such as astronomy, has no impact on our everyday lives, but is interesting in what it tells us about our universe. The task here is to report it in an interesting and informative way.

- You must always be accurate. Science is built on accuracy.

- Your readers or listeners usually trust science. Often, in fields such as medicine, their lives may depend on it. You should not alarm them by making sensational claims which may not be true.

These are some general rules. How can you apply them in practice?

These are some general rules. How can you apply them in practice?

^^back to the top

The basics of reporting

You should use the same techniques for good journalism we have discussed earlier in this book. In particular, when reporting science and technology, you should remember the following:

Build up a basic knowledge

Science and technology is a huge field, but each subject usually has some basic rules which govern it. If you understand these rules, you will be able to work out the rest of the topic, even though you will not understand all the details. In medicine, for example, you need to understand the basic parts of the body and their functions. You do not need to know all the ingredients in blood, but you should know that blood is the main system of transporting nutrients, chemicals and waste throughout the body.

A good high school education in science should give you enough knowledge of the basic rules to get started. After that, you must take every opportunity to increase your knowledge.

Read widely

Science and technology advance so quickly that you must keep up to date. Read articles on science and technology. Read books on basic science (encyclopedias are a good place to start). Avoid textbooks which are too complicated. Instead, look for books which explain their subject in simple terms for ordinary, non-scientific readers. Ask people expert in each field for advice on the best books for your needs - something clear and simple.

Make contacts

Get to know as many scientists and technologists as you can. They can give you advice on subjects you do not understand and, like any good contact, they will be a useful source of story ideas.

Do not expect an expert in one field to be able to help in another. Few electrical engineers, for example, will know what lymph glands do in the body. Make as wide a range of contacts as you can, across all the fields of science and technology.

Choose people who can give you (a) story ideas, (b) background information and (c) the names of people you should ask for further details.

Try to establish at least one contact from each major scientific field (such as medicine, environmental science, agriculture and fishing, geology, engineering or any other fields which are especially important in your society). Keep in regular contact with them.

You can quote them in your stories if they are experts in the particular field about which you are writing, but it is better to go to the expert who is best able to give you the specific information you need.

Some scientists are better at explaining their work in simple terms than others. When you are researching a story, go to the contact most suited to your particular need. For example, one zoologist may be able to explain the background to a new development, but you may have to ask the head of the university department or the director of the research station for any official comments.

Do not forget that scientists often work in teams. If one member cannot help, another might be able to.

Technicians and laboratory assistants can be a very good source of story ideas, but do not rely on them for the official version of a story. If they give you a story idea, seek out the scientist concerned for details.

Building trust

Many scientists do not trust journalists. They may not think you are capable of reporting their work properly or they may have had a bad experience with a journalist in the past. They may have been misquoted or seen errors in a story.

You have to show that you can be trusted. It will help if you do some background research of your own before interviewing them, so that you can show you know the basic facts about their field.

It is not enough to tell them you can be trusted; you have to show it in every story that you write. If you make careless errors or do not keep a promise, you will lose their trust for ever.

Dig for the truth

Being friendly does not mean you have to believe everything a person says. Much of science is built on experiments and on trial-and-error. In many fields, a number of scientists may be working on the same topic, and may reach different conclusions. They are often competing against each other to be the first with a result. They may occasionally make big claims to show how important they are or to justify money being spent on their research.

Be especially careful about scientists who say their work will benefit mankind. In many cases it will, but in others it may not. For example, a scientist may tell you that a new drug will help people to relax, but he may not tell you that it increases their risk of getting cancer. The side-effects of science can be more damaging than the benefits from it.

Therefore, you must question their claims by asking probing questions. If you still feel unhappy about what you have been told, go to other experts in that field and ask for further information.

Be sceptical

Both science and journalism are based on being sceptical and questioning what people say. Galileo would never have proved the world was round by believing what most other scientists of his era were telling him. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein would never has exposed the corrupt Watergate Scandal if they had trusted the White House press denials. As a journalist with the power to influence people, you will be asked to accept at face value all sorts of claims.

Science and technology companies will offer you all sorts of free samples, advice and even prepared news stories to promote their products. They will disguise this by saying these are important medical breakthroughs. Always question their claims and always balance what they say by seeking and reporting opposing views. Drug manufacturers and research companies are increasing offering television journalists ready-made and professionally-packaged news reports of a new medical breakthrough or wonder drug. In many cases they may be beneficial but a good journalist – like a good scientist – must always ask hard questions and inform readers and listeners honestly and fairly. Do your own work, even use some of the video footage if it is relevant – then go out and get alternative views to balance or moderate the claims.

^^back to the top

Newsgathering

Once you have established some basic knowledge and good contacts, you can put them to work in reporting science and technology. Your task will not be too different from reporting general news, but there are some essential elements to focus your attention on if you are to report science and technology successfully.

Is it about people?

Wherever possible, look for the human angle in your stories. The human angle can be about any or all of the following:

- The people who will be affected by the development will often be your readers or listeners; the people who eat bread made from a new variety of corn or patients who can now be treated with a new piece of medical equipment.

- The people who use the new developments directly will usually be interested in any new resources and they might make interesting subjects for stories themselves. The farmers who use the new corn seed or doctors who use the new instrument will be of interest to others working in similar areas.

- The scientists or technologists responsible for the development or discovery can make interesting human interest stories. Perhaps their work has been long and difficult; perhaps they discovered the new seed or the principles behind the new instrument by accident. They are human beings, probably excited by their work, and so may make interesting subjects for stories.

A word of warning, however: Do not bury the importance of a development beneath details of the scientists who developed it. By all means explain about the scientists' search for a new drug to fight cancer, but remember that most of your readers or listeners will want to know about the drug itself, and its possible effects on their lives.

Understanding the details

As we mentioned earlier, you must understand what you are told before you can write clearly and accurately about it.

It is always wise to prepare for any interview. Before interviewing a scientist, make sure you know the basics of his or her field. Meteorologists will not be happy if you think they look for meteors. If you do not have information available, why not ask one of your contacts for some basic background facts before interviewing your chosen scientist?

Science can often be too complicated to explain over the telephone. If you are not entirely clear, visit the scientist yourself and get them to sit down with you, to explain the details until you understand.

It often helps if they show you the new chemical or equipment, the plant or animal involved. Get them to draw diagrams. If their diagram helps you to understand, why not include a diagram in your story for newspapers or television?

If, when you are back at your desk writing the story, you discover that there is still something you do not understand, contact your scientist again and ask them to explain. You may find that they have forgotten to tell you or that your notes are incomplete or incorrect.

Some reporters actually show their story to their informants before publishing it. This is more common in feature articles than in hard news stories. If you do this, you must make it clear that they are only being asked to check the facts. You must not allow them to dictate how you write the story. They may be the experts on science or technology, but you must be the expert in what is newsworthy.

It will help if you explain your needs clearly to your informants before you start interviewing. You can explain whether this will be a lengthy feature, a documentary or just a short news item. You can also explain who your audience will be and how simple (or complicated) the information needs to be. This will avoid a lot of misunderstanding and possible bad feelings.

For example, you may interview a botanist about a new type of disease-resistant seed-corn she has developed. She may give you lots and lots of detailed information about it, enough to satisfy the readers of a farming magazine, when all you need are a few basic details for a general news story. Unless you have warned her first, she may be upset about how little of her information you eventually use.

Remember, most scientists are so involved in their work that they often cannot understand that everyone else - especially you and your readers or listeners - do not have the same depth of interest.

News sense

Scientists are usually very clever and know a lot about their own subject, but they are not trained like you to recognise a news story. They may feel that their own work is not newsworthy or they may disagree with you over what is the real news angle in their research.

You must always be on the lookout for news stories in everything you hear or read. Perhaps a casual conversation with a visiting professor might give you an idea for a story. Perhaps you will find clues in the agricultural college's annual report. There are news stories everywhere in science, just waiting for you to spot them and bring them into the light. Your contacts may be able to spot a news story for you, or they may be able to give you help once you take your story idea to them.

Some scientists may disagree with you about the news angle you are taking on their particular information. The botanist may believe that the breakthrough for fellow scientists is the most important aspect of her new seed, whereas you see it more from the angle of the farmer or the person who eats bread. Always listen to the scientist's advice, but you cannot always follow it, because your job is different to theirs. Try to convince the scientist to look at the story from the point of view of your readers or listeners, and they will usually cooperate.

Objectivity

Like many things in life, science can have good and bad effects. And like many things, people will disagree about what these are. Your job as a journalist is to report the facts as known in a fair and honest way. You should not take sides on issues, unless you are writing a commentary column for your newspaper.

This is especially important in controversial areas such as the environment or medical ethics, where even the experts will disagree. And always be wary about people who try to get your help as a journalist to present only their side of a scientific argument. Give all sides and let your readers or listeners make up their own minds.

For example, if you write a story about a new wood pulp mill, you obviously need to talk both to the company and to any environmental opponents. But you should also speak to the local people and perhaps the government for their reaction. Try to cover every aspect of the story and present them all fairly.

Reporting agriculture, fisheries and forestry

Farming, fishing and forestry are three of the most important forms of human activity around the world and play vital roles in the economies of developing nations, where they are still major employers of people, as agricultural labourers or as small farmers cultivating their own land or as fishers with their own boats and nets or crewing for other people. For this section and for convenience, unless otherwise specified we will include fishing and forestry under agriculture as three similar parts of what are collectively called primary industries (the other main sector is mining).

In developed nations, agriculture no longer employs the proportion of the workforce it once did - due largely to increased mechanisation, larger-scale farms and the use of chemicals and advanced farming science. However, as the world’s population grows, farming everywhere is being forced to innovate to feed millions of extra mouths every year. It is therefore important to all countries for information about agricultural development to be shared so farmers can increase their crops and improve their yields and the quality of their livestock.

The media play a crucial role in the dissemination of information about new technologies and techniques as well as about the spread of threats such as blights, insect predation, livestock diseases and climate change. While most nations have departments of agriculture to educate farmers and alert them to advances and dangers, the media can often reach into the lives of working farmers more widely and quicker, with well-written articles or broadcasts attracting their attention. It is also important that non-farming citizens and consumers get to read and hear about what is happening in farming and fishing, so they will understand how food gets onto their tables, why produce prices change and why there might be shortages or gluts.

And while professional farmers require quite detailed information to run their farms, everyone needs reporting that is informative while also being simple and direct enough to understand. It is therefore important for agricultural reporters to know their specific audience. If you write for a farming newspaper or specialist radio program you will need to present quite a lot of detailed information in a way that ordinary farmers can understand, but if you write for a more general, non-farming audience you will need to simplify your stories so ordinary readers and listeners get the required information without being inundated with too much detail.

The News Manual does not attempt to give advice on specific industries – including farming, fishing and forestry – though you will find useful guidance on covering “rounds” (special interest areas) in Volume 2, especially Chapters 26 on Rounds, 29 on Industry and Finance, 30 on Economics and 32 on Writing about Science & Technology.

You can also find more help on specialist sites such as the International Federation of Agricultural Journalists (IFAJ), a politically neutral, not-for-profit professional association for agricultural journalists in 56 countries. https://www.ifaj.org

For journalists starting out in agricultural reporting, science journalist and freelance reporter Aleszu Bajak, interviewed for the International Journalists Network (IJN), had this advice: “Find a local story or a local component to a global issue. Start talking to farmers, producers, middlemen, researchers, scholars, scientists, policymakers. Wrap your head around the issues. Look at the prior stories and remember the strengths and weaknesses of those pieces. Look at video, podcasts, op-eds, scientific studies, there's plenty out there. The more informed you are, the more your sources will confide in you. Get your hands dirty. Go to the farm or the lab or the conference or the docks. Note the details. Talk to the workers and their supervisors. Take copious notes. And keep a sceptical and open mind about everything you read and everyone you chat with. People have their priorities and yours is the truth. Be nice. Don't demonize people.”

Rian Bosse, writing for the National Center for Business Journalism, has five short tips for covering agriculture.

If you need to really dig deeply into coverage of agricultural news, Washington State University has published an Agricultural Style Guide for Journalists, with agricultural terms, definitions, equivalencies, and a guide to use, by Terence L. Day (retired). This list is provided for journalists who write about agriculture for the general public.

Given the impact climate change is having on agriculture and food production, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) has produced a useful book “Getting the message across: reporting on climate change and sustainable development in Asia and the Pacific; A handbook for journalists.”

TO SUMMARISE:

You must understand the basic principles of any scientific field before you can report in it; you can get that understanding by:

- Having a basic scientific education

- Reading books and magazines about science and technology

- Taking an interest in scientific and technological developments

- Establishing good contacts with experts who can help you with information

This is the end of the first part of this twoi-part section on science and technology. If you now want to read on, follow this link to the second section, Chapter 32: Writing about science and technology

^^back to the top